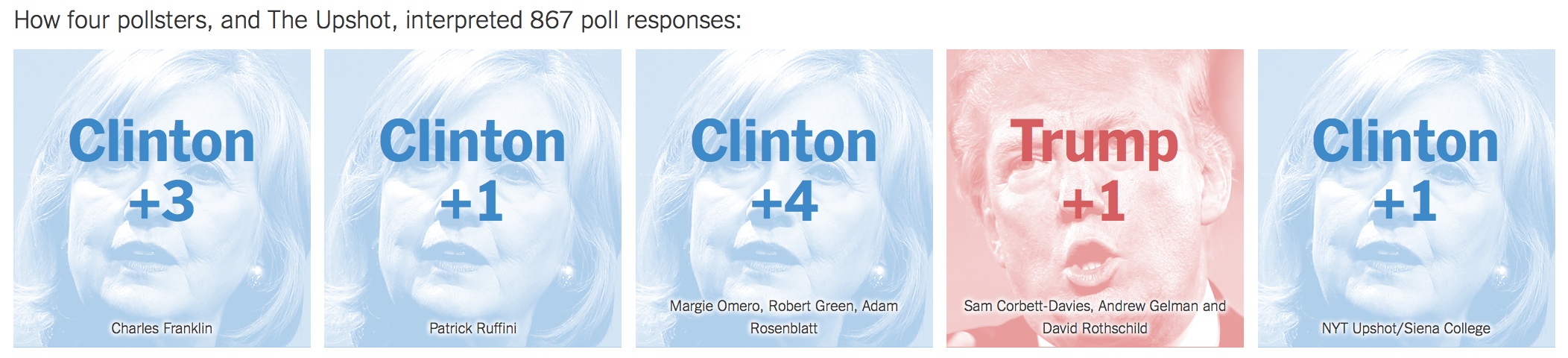

The New York Times published an interesting piece on the differences between pollsters’ predictions. All five predictions used the same data set, so sampling differences are not of concern. Still, there was a difference of up to 5% between the predictions.

How so? Because pollsters make a series of decisions when designing their survey, from determining likely voters to adjusting their respondents to match the demographics of the electorate. These decisions are hard. They usually take place behind the scenes, and they can make a huge difference.

This is a very good example of the “garden of forking paths”, a term coined by Andrew Gelman who was also involved in one of the predictions.

Pollsters, however, have one advantage over scientists: there will be a “true” outcome at election day, so the model can be checked and adapted for the next election cycle. While this is still a bias towards “expected results”, I think, it is not as troubling as in the empirical sciences, where we are having a hard time to securely validate our theories, models and predictions through numerous replications.1

The NYT article is helpful to understand, that “margin of error”, which means sampling error, is only one part of the overall error and that different pollsters will come to different conclusions also because of their methods. That’s why FiveThirtyEight’s forecast is quite interesting: As they also sample polls they have some methodological variability in their data set. They further aggregate non-poll data (such as state economy) to come up with their predictions.

I am very curious how closely the polls will match the election results. In Europe, recent elections have shown some bias against non-mainstream positions such as right-wing parties: British polls did not expect Brexit to happen and in Germany the AfD has gathered more votes than polls expected them to do in two state elections. I think, both are an example of the bias towards the status-quo.

- One could also say, that the history of a particular pollster model is a strong prior with weight on expected results: You need a lot of data telling you otherwise to change your opinion. This might be a problem in the current US presidential election: No-one seriously expected Trump to get so far and the models are only slowly adapting to the many poll participants who would vote for Trump. But this is just an interpretation of what’s happening without data to back this idea up. ↩